Uprating Local Housing Allowance: Briefing Note

On this page

The report is published in full on this page. Click here 400 KB to download a pdf version, and click here to download an editable Google doc version.

The 4-year freeze had a detrimental impact on the people we support

Local Housing Allowance (LHA) is the mechanism by which Housing Benefit (HB) and the Universal Credit housing element (UCHE) are calculated for private renters[1]. The freezing of LHA from 2020 (and other reforms since 2010) meant support for housing costs within the benefits system decreased, causing significant hardship among many of the people Citizens Advice supports.

The single-year uprating in April 2024 has not undone all of the impacts of recent LHA policies, and re-freezing LHA from LHA from April 2025 would cause additional hardship.

Box 1. A recent history of Local Housing Allowance

LHA is the mechanism by which HB or UCHE awards are calculated for private renters. If you receive income-related benefits, LHA determines how much support with rent you will receive. The calculation is based on rental costs in the area where a person lives, for the type of property (ie number of bedrooms) they need.

When rolled out in 2008, LHA was set at the median (or 50th percentile) rent cost, differentiated by ‘broad rental market area’ (BRMA), as calculated by local valuation offices. In 2011, the reference point was reduced to the 30th percentile, and a national cap was introduced so that housing cost support could be restricted irrespective of local rent costs. In 2012, the application of the lowest LHA rate, the Shared Accommodation Rate (SAR), was extended from under-25s to under-35s (if they were single and did not have children).

LHA rates were then decoupled from local rents in 2013. LHA was uprated annually by inflation or 1% (ie below inflation), or frozen altogether. A 4-year freeze from 2020 onwards finally ended in April 2024, when LHA was relinked to the 30th percentile of local rent costs for a single year.

Shortfalls during the freeze

By the end of 2023/24, the impact of the 4-year freeze could be seen in the fact that almost two-thirds (65%) of UCHE recipients in the private rented sector (PRS) experienced a shortfall between housing cost support and their actual rent costs.[2]

Shortfalls were more likely to be experienced in some regions than others. The proportion with a shortfall was above 70% in both Midlands regions and the 3 regions of the North of England, and highest in Wales (77%).[3]

Among people seeking our advice on debt issues, the average LHA shortfall for UCHE recipients in the private rented sector was £157 per month in 2023/24.[4] Our report 'The Impact of Freezing Local Housing Allowance'[5] outlined several specific impacts on the people we support, including:

A greater risk of eviction and homelessness.

A reliance on poor quality housing, often exacerbating health problems.

Difficulty finding or maintaining work.[6]

Less money to spend on essentials such as food and energy.

A need to use benefit income designed to cover health-related costs on housing costs.

Mental health problems resulting from constant concern about rent payments.

DIfficulty in accessing Discretionary Housing Payments (DHPs), intended to help people in rent arrears.

Grace* lives in London with her three children. She was evicted from her home as her landlord wanted to sell the property. Her family had to move into a B&B, which was far away from her children's schools, and had no cooking or washing facilities. 1 of her children was being treated for a serious medical condition, potentially triggered by the stress of their housing situation. Grace tried to find alternative private rented accommodation, but was unable to find anything that was affordable within her LHA rate, even when looking at 2-bed properties. She considered moving out of London but was worried about the impact on her children’s education, 1 of whom is currently sitting exams.

Corinne* lives in the North of England in a privately rented property. She had a shortfall between her LHA rate and her rent of around £50 a month. Corinne came to us after her landlord told her the rent would be increasing by an additional £200 a month. She has severe mobility difficulties and receives Personal Independence Payment (PIP) to help cover the additional costs associated with her disability. However, she was having to use this money to pay her rent each month. With the rise in rent, even her PIP payments did not cover her shortfall, and she was worried about her ability to keep paying her rent, cover her health costs, and maintain a basic standard of living.

Problems with the SAR

People eligible for only the SAR (who are supported to rent a single room in shared housing) are among the worst affected groups. 88% receiving HB or UCHE had a shortfall as of November 2023 (and this is discounting those who would be eligible for housing cost support at the SAR level, but cannot afford to move out of their parental home in the first place).[7]

Among people seeking our advice on debt issues, the average LHA shortfall for UCHE recipients in the private rented sector only eligible for the SAR was £250 per month in 2023/24 – almost £100 more than across all LHA categories.[8] Our report An Unfair Share[9] detailed the impacts of the SAR, including a greater risk of eviction and homelessness – the number of young people seeking our advice on homelessness issues has risen sharply in recent years – and the barriers to developing an independent life it creates for some young people.

“The Shared Accommodation Rate is pitiful compared to [the cost of] the average rentals” – Citizens Advice adviser, August 20204

The SAR takes no account of the volume of shared housing available in a given area. If there are too few rooms in shared accommodation to rent, many people eligible for only the SAR will be required to rent more expensive properties (ie 1-bedroom flats) despite receiving a lower rate of housing cost support. This is potentially a problem for the LHA system as a whole, but the scarcity of shared housing makes it particularly problematic for people eligible for the SAR.

The requirement to share accommodation also contributes to mental health problems, and is particularly problematic for refugees granted leave to remain, and separated parents who are not the primary carer for their children but who are nevertheless required to provide a family home.

Chris* found housing cost support limited to the SAR insufficient to live on, even in shared housing. To reduce his housing costs, he had moved in with a friend, reducing his monthly rent to around £450. However, he lives in an area of England with the lowest rate of the SAR, meaning that he was paid just £55.02 a week towards his housing costs. Even after taking action to change his housing situation and find shared accommodation, the SAR still left him with a significant shortfall in his housing costs. The rate he is paid increased in April to £73.35 per week, but this still left him needing to find £128 per month to make up the difference. Chris was already in debt, a situation which was likely to worsen as he continued to receive less than he needed to pay his rent.

Diane* lives in a bedsit in central London. She came to us after her landlord increased the rent from £650 a month to £1000 a month. What had been affordable within the limits of the SAR was no longer affordable, and she had been threatened with eviction as a result. She struggled to find alternative accommodation that was sufficiently close to her place of work, meaning that she would have had to rely on homelessness support services from her local authority in order to maintain her employment.

The wider context

The LHA system is part of a wider set of problems in the PRS. The average cost of renting privately in the UK grew sharply by 9.2% in the year before LHA was uprated, on top of a 6.2% increase in the year before.[10] Citizens Advice analysis shows that low-income private renters are expected to spend nearly half (44%) of their income in 2024/25 just on rent – compared to 36% for those in social housing, and 26% of mortgage holders.[11]

In our July 2024 report on the PRS, 'Through the Roof', we reported on a nationally representative online survey of 2,000 private renters in England conducted by YouGov in June 2024. The survey showed that:

More than half (52%) of private renters have faced a rent increase in the last year – on average by £50 per month, with 1 in 5 facing a monthly hike of more than £100, and 11% more than £200.

Almost half of renters are living with damp, mould or excessive cold.

Almost three-quarters of those facing rent hikes didn’t complain to their landlords – with half of them saying it was for fear of eviction or other landlord retaliation.

39% of renters have cut back on heating, food and other essentials to pay their rent.

A third of renters have had to use credit and other borrowing to cover their rent. 12% have fallen into debt on essential bills like energy, water or council tax in order to pay their rent.

Amongst our debt clients, private renters now have record levels of overall debt – £8,364 on average, up 29% since the start of the cost-of-living crisis in 2021. This is almost £1,000 higher than the average debt for social renters (£7,370).[12]

It is clear that conditions in the PRS must be addressed by the government. The government has committed to provide more support to people in the PRS, and the Renters’ Rights Bill will improve housing standards, as well as making it more difficult to evict tenants. But even if this programme succeeds, it is unlikely to reduce the cost and risks of renting privately in the short term. Investment in social housing will not be increased in the short term, and there are no plans to introduce rent controls. The most effective route to support private renters financially now, and probably for the foreseeable future, is via the benefits system.

The April 2024 uplift has not delivered the intended benefits

In April 2024, LHA was relinked to the 30th percentile of local rent costs, facilitating an average 16.6% rise in the maximum housing cost support available (with variation across BRMAs as well as the different LHA categories). However, for several reasons, most households do not actually receive housing cost support at this level.

Capped support

The LHA cap and the benefit cap prevent many households receiving their entitlement to housing cost support even where their rent costs are at or above the relevant LHA rate.

LHA cap:

The national cap on housing cost support means that LHA rates can be limited irrespective of the calculations of the 30th percentile by valuation offices. In 2024/25, LHA rates in several BRMAs, across various LHA categories, are set below the 30th percentile level to avoid breaching the national cap.

The cap is being applied to all LHA categories in Central London and Inner North London apart from the SAR. It is being applied to the 1- and 3-bedroom categories in Inner East London, and to the 3-bedroom category in Inner South West London.

We estimate that there are more than 14,000 families with children receiving UCHE who are subject to the cap in these areas.[13] We estimate there are also more than 23,000 households with no children receiving UCHE subject to the cap in these areas.[14]

It is also worth noting that the ‘highest’ category in the LHA system is the 4-bedroom rate. Households can only access this rate even if their family circumstances (eg the number of children) mean they need more than 4 bedrooms.

Alex* lives with his partner and 2 children in London. Despite health problems, he works full-time earning the National Living Wage. He is therefore exempt from the benefit cap, but the national LHA cap means he has a housing cost support shortfall of more than £200 each month. He is trying to manage rent and energy bill arrears, as well as personal loan repayments, and has around £150 deducted from his benefit payments each month for overpayment recovery.

Benefit cap:

The benefit cap is more likely than the LHA cap to affect larger families, such as those requiring the 4-bedroom rate, since they are more likely to receive higher UCHE payments (even if the 2-child limit restricts their Universal Credit payments more generally).

There is only limited data available publicly on the application of the benefit cap. However, we can calculate that, for a couple who are both out-of-work, receiving the Universal Credit child element (UCCE) for the maximum of 2 children born after April 2017, and UCHE at the maximum rate for their BRMA, their Universal Credit income would breach the benefit cap in 100% of BRMAs in England in 2024/25 if they require a 4-bedroom property.

However, the impact of the benefit cap is not restricted to large families. This couple’s Universal Credit income would breach the benefit cap in 83% of BRMAs if they require a 3-bedroom property, and in 65% of BRMAs even if they only require a 2-bedroom property.[15]

The proportions are lower for single-parent households, but still remarkably high. For a single person who is out-of-work, receiving the Universal Credit child element (UCCE) for the maximum of 2 children, and UCHE at the maximum rate for their BRMA, their Universal Credit income would breach the benefit cap in 78% of BRMAs in England in 2024/25 if they require a 4-bedroom property.

Their Universal Credit income would breach the benefit cap in 48% of BRMAs if they require a 3-bedroom property, and in 33% of BRMAs if they require a 2-bedroom property.[16]

In the year to June 2024, 41% of the people we supported with benefit cap issues were private renters, compared to 24% of people we support with all benefits issues.[17] The number of people we are supporting with benefit cap issues was marginally higher (3%) in June 2024 than June 2023. The figures for April, May and June 2024 are all higher than every single month in the financial year 2023/24.

Over the same period, 35% of the people we supported with benefit cap issues were single parents, compared to 20% of people we support with all benefits issues. 38% of the people we supported with benefit cap issues also needed support with debt issues, and 37% needed charitable assistance including food bank referrals.

Zain* lives in the South West with his partner and 5 children. He is presently unable to work due to ill-health, and 2 of his children are disabled (he is applying for Personal Independence Payment (PIP), and he is awaiting Disability Living Allowance decisions for his children). His LHA rate is £400 per month below his rent costs, and he has a Universal Credit deduction for a previous breach of capital limit - even though he has now spent all of the savings he is being penalised for on essential living costs. However, uprating LHA or altering his deduction would make no difference to Zain, because his overall benefit income is capped at a level just above his rent costs. A demand for up-front rent payments from his landlord means the family is at risk of eviction, and they are reliant on food banks.

Sandra* lives alone in London. She has mental and physical health problems, and is applying for both PIP and Universal Credit’s Limited Capability for Work-Related Activity element. Sandra did not benefit in full from LHA uprating in April due to her income being pushed above the benefit cap. She is struggling to pay off debts and cover her energy bills, and has become dependent on food banks.

Data limitations

It is not clear that the data underpinning LHA rate calculations offers a true picture of rent costs across different areas. There are 4 main issues:

Local valuation offices rely on rent data supplied by private landlords via surveys. There is little information publicly on sampling methods and response rates. The 30th percentile would be set at an artificially low level if, for instance, data were disproportionately collected from owners of more expensive properties.

The data used to calculate LHA includes all rents in payment. But asking rents are invariably higher, because landlords implement rent increases between tenancies. As such, people who are looking for a new place to live – if they have, for instance, been evicted – will usually be expected to pay a higher rent price than the LHA system recognises.

Properties being rented to people in receipt of HB or UCHE are excluded from LHA calculations. Since these properties are more likely to be at the lower end of the rent cost distribution, again this means the 30th percentile would be set at an artificially low level.

BRMAs may encompass areas with distinct PRS market characteristics. For example, data from a town with relatively low rent costs could affect the calculation of the 30th percentile in a nearby town with high rent costs. People receiving housing cost support in the latter town would be disadvantaged by their LHA maximum being set below the 30th percentile for the area they live in (and note that they may need to stay in this higher-cost area to access employment opportunities).

Data limitations are particularly evident in relation to the SAR, as reported in 'An Unfair Share'. The main problems are:

The SAR is calculated using a very low number of data points (eg across BRMAs in England there are on average 10 times as many data points used in the calculation of the 2-bedroom rate of LHA). This reflects the scarcity of shared housing, noted above, but also indicates that calculation methods are unreliable. The SAR tends to be quite volatile as a result, with the decisions of a small number of landlords to enter or exit this market, or change their prices, having a significant impact on calculations.

There is a lack of transparency in terms of how the shared housing market is defined for LHA purposes. For example:

a) Student accommodation in the PRS would meet the definition of shared housing, and tends to be low-cost. But it is not typically available to benefit claimants, despite, it seems, being included in the calculation of the 30th percentile.

b) It is not clear whether joint tenancies are included in LHA calculations, or whether practices differ across BRMAs in this regard. This is a very common form of housing for young adults, but since the tenants are jointly renting an entire property rather than being responsible for only a single room, it may not qualify as shared housing for the purpose of LHA.

Implementation lag

In order to determine the 30th percentile rent cost in each BRMA – irrespective of whether the link is being applied in practice – local valuation offices collect rent data by surveying landlords over a 12-month period from October to September.

If LHA is being uprated in line with the original policy intent, the newly calculated LHA rates are implemented in the following April. This means that some of the rent cost data underpinning the LHA rates applied in April 2024, and remaining in place until at least spring 2025, will have been collected in autumn 2022 (and no later than early autumn 2023).

This is particularly problematic at a time of steep rent rises. Even based only on the end of the data collection period, private rent costs in the UK grew by around 5% between September 2023 (when uprated LHA rates were fixed) and April 2024 (when the new rates were implemented).[18]

Across BRMAs in Britain, the LHA rates applied in the financial year 2024/25 would have covered only 8.5% of asking rents in the PRS published by Zoopla in the calendar 2023. Broken down by LHA category, the relevant 2024/25 LHA rates would have covered only 15.7% of 1-bedroom properties, 4.8% of 2-bedroom properties, 4.3% of 3-bedroom properties, and 9.8% of 4-bedroom properties.

Broken down by nation, the LHA rates applied in 2024/25 would have covered only 8.2% of 2023 asking rents in England, 14.9% in Scotland, and 5.5% in Wales.[19]

It should also be noted that, for UCHE recipients, the application of higher LHA rates in April 2024 does not necessarily lead to higher UCHE payments immediately. The new rates were applied to monthly assessment periods beginning from 8th April onwards. If someone has an assessment period beginning on, say, 7th May, they would not see an increase in their UCHE payments until receiving their Universal Credit payment in arrears shortly after their assessment period ends on 6th June.[20]

People are still struggling with inadequate housing cost support

It is clear that the April 2024 uplift has not solved the problem of inadequate housing cost support. Re-freezing LHA for 2025/26 would intensify this problem and cause significant hardship.

People seeking our support

There has been a small dip in the number of people seeking our help because their LHA maximum rate is too low. The July 2024 figure was only 9% below the equivalent period in 2023. While we can presume that the April 2024 uprating has had a positive impact for some people, it has not led to a significant reduction in the number of benefit claimants with rent shortfalls that are difficult or impossible to manage.

“We had expected the rise in LHA to result in people being able to find rents within the limit but generally that does not appear to be the case.” – Citizens Advice adviser, August 2024

“The uprating of the LHA has had a marginal effect on affordability. However we are checking our local [asking] rents every month and the uprated LHA is not covering the 30% it is supposed to. In the first quarter [after LHA was uprated] only 1 property was within the LHA and in the second quarter about 5 were covered.” – Citizens Advice adviser, August 2024

The number of PRS residents seeking our support on HB or UCHE in general continues to grow. We helped 11% more people in this group in July 2024 than in the equivalent period in 2023. The number of PRS residents we help with homelessness issues also continues to rise. We helped 12% more people in July 2024 than in the equivalent period in 2023 in this regard.

We also continue to support a large number of PRS residents with DHP issues. DHPs are the means by which people facing immediate housing crises can apply for additional financial support (these payments are administered by local government but funded by a specific allocation from central government). We helped around 14% more people with DHP issues in July 2024 (almost 4,700 people) than we did in the equivalent period in 2023.[21]

David* is in his early-60s and lives in Wales. He recently had to leave his job due to ill-health, and is applying for disability benefits. Currently he receives only the Universal Credit standard allowance and housing element, but his rent costs are significantly above his LHA maximum rate. He has become reliant on DHPs and is struggling to pay off several private debts.

Our advisers have reported that rent shortfalls remain a significant problem for the HB and UCHE claimants they support. Almost 6 in 10 (57.2%) responding to a survey in August 2024 report they are helping more people experiencing a LHA shortfall, and more than a third (36.8%) report they are helping around the same number of people, since LHA rates were uprated in April.[22]

“The uprating was very welcome, but is just out of touch with actual rent increases.” – Citizens Advice adviser, August 2024

More than two-thirds (67.5%) of respondents report that, among private tenants receiving housing cost support they are helping, most or all have experienced rent increases since September 2023, when the latest rent data underpinning current LHA rates was collected. A further 1 in 5 (20.5%) report that around half have experienced a rent increase in this period.[23]

“At the moment the uprating of LHA is not making a bit of difference [to our clients] as private rents have soared to an extortionate amount.” – Citizens Advice adviser, August 2024

Nicola* lives in the North East with her 2 young daughters, and also has caring responsibilities for her older son. She is unable to work due to mental health problems, and 1 of her daughters is disabled - she has begun the process of applying for disability benefits. She is entitled to the LHA 2-bedroom rate, but her rent was already above the new rate introduced in her area in April 2024. Nicola’s landlord then raised the rent from £600 per month to £750 per month in June 2024, creating a shortfall of around £200 per month that she cannot afford to cover.

Ongoing shortfalls

Government data shows that LHA uprating has had a positive impact on the proportion of UCHE recipients in the PRS seeing a shortfall between housing cost support and their rent. However, it is still the case that 44% of claimants in this group have a shortfall.[24]

And this does not take into account the impact of the benefit cap: even those who do not have a shortfall in their nominal housing cost support payments may be receiving less than they need in practice, if the cap subsequently restricts their overall benefit income. Between February 2024 and May 2024, there was a 61% increase in the number of households with their benefits capped, and the average monthly loss due to the benefit cap increased from £221 per month to £255 per month.[25]

“People cannot meet the shortfall despite the increase in the LHA. Those who can manage the shortfall tend to be those getting a disability benefit and end up using Personal Independence Payment, for example, to meet the shortfall when this is supposed to be there to meet the extra costs of disability.” – Citizens Advice adviser, August 2024

All of the regions of the North and Midlands of England, and Wales, have proportions above this national figure. Breaking down the data by number of children, households with 2 children are most likely to have a shortfall (47%).[26]

John* lives alone on the South coast of England. He is in receipt of the state pension, Pension Credit and HB. In July, John’s landlord informed him of their intention to increase his rent to £800 per month, which would leave a shortfall of more than £200 per month due to being above the local LHA rate. John is on the waiting list for social housing but is not a high-priority case. At best, he will be forced to leave the area he lives in to seek a cheaper home in the private rented sector, despite ongoing medical issues.

National Red Index analysis

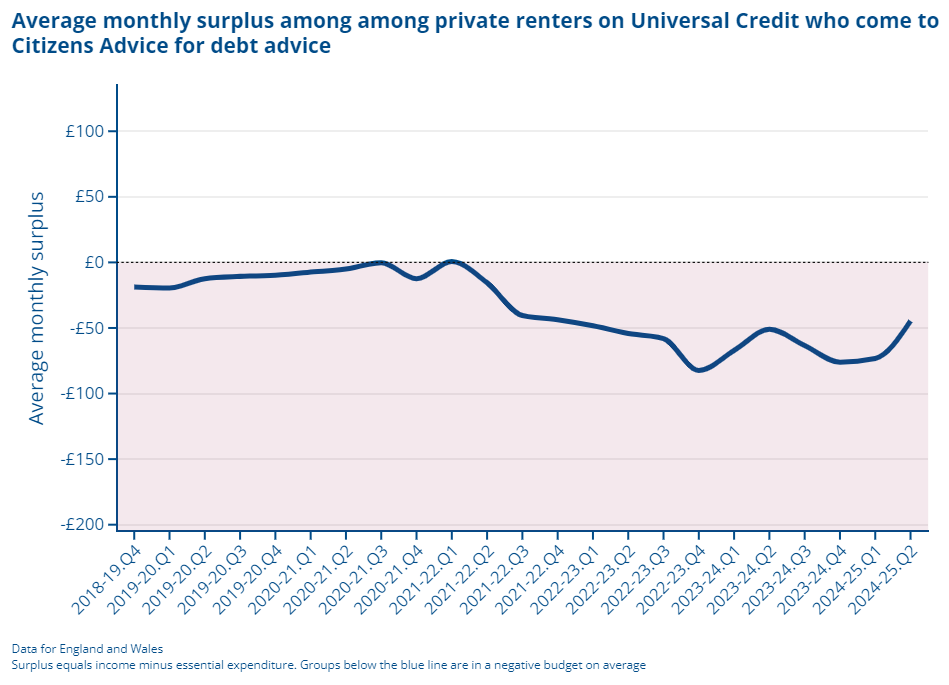

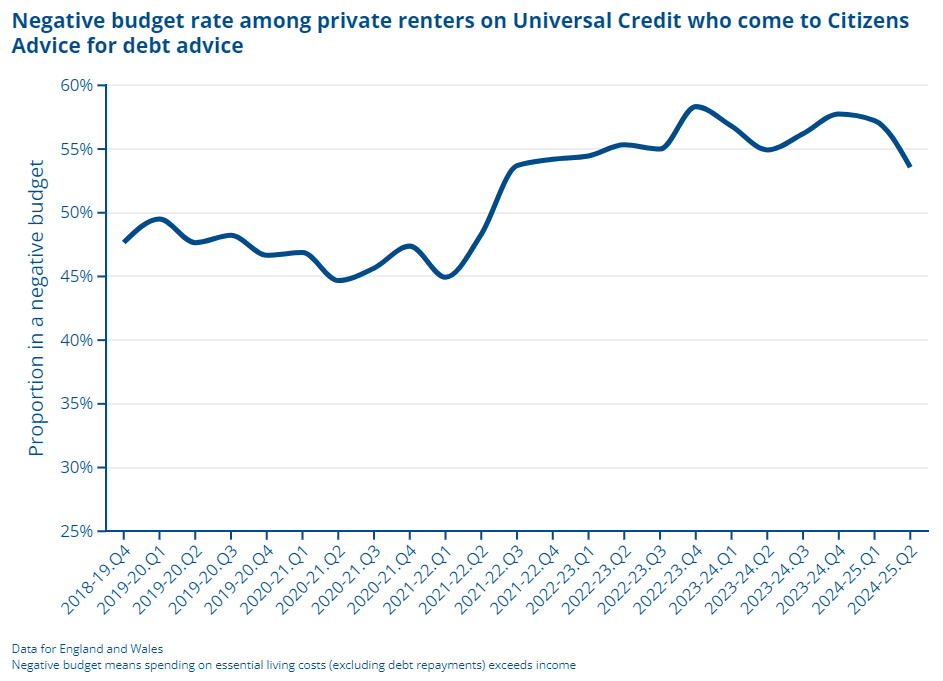

We know that housing costs – rising sharply while LHA was frozen – have been a significant driver of negative budgets in recent years. Budgeting data from the people we help with debt issues indicates the positive impact of uprating LHA in 2024 (alongside the uprating of most benefits in line with inflation). Yet gains have been insufficient in many cases to lift people out of negative budgets, meaning they continue to spend more than their income each month, despite minimising their expenditure as much as possible.

The average monthly deficit for our debt clients, receiving Universal Credit in the PRS, has fallen from £76.09 in the fourth quarter of 2023/24 (before uprating) to £44.70 in the second quarter of 2024/25 (when we know uprating will have been fully implemented). Deficits may generally be lower, but the proportion of this group with a negative budget – unable to meet essential living costs, let alone repay debts – only fell from 58% to 54%.[27] Most of this group are still in the red.

Our National Red Index (NRI) – which applies what we know about our debt clients to Living Costs and Food Survey data to create a nationally representative sample[28] – suggests that while the 2024 uprating will have helped many people to address LHA shortfalls arising from rent increases in 2024/25, it has done little to tackle existing shortfalls built up during the LHA freeze.

In general, benefit uprating is supposed to compensate people for cost-of-living increases they have already experienced, which will have eroded the real-terms value of their benefits income. This is why LHA rates, for example, are uprated in relation to outturn rather than forecast rent data. However, the 4-year freeze meant LHA ceased to perform this function, and incomes remain a long way from catching up.

NRI data shows that, by the end 2024/25, 43% of people in the PRS, receiving means-tested benefits, will have completely used up the additional income due to LHA uprating on addressing rent increases in this financial year. They will have no opportunity to reduce the existing shortfalls that had built up by April 2024.

And even for the 57% of this group for whom 2024/25 rent increases do not entirely consume the additional income, on average they have only £19 remaining each month – falling far short of the income needed to overcome existing shortfalls.

Policy options for the next budget

The Price Index of Private Rents (PIPR) shows that private rent costs in the UK grew by 8.24% between April 2023 and March 2024 (used as approximate monthly mid-points of the October 2022-September 2023 and October 2023-September 2024 data collection periods for the latest and next LHA calculation processes).[29]

The government has 3 main options when deciding whether to uprate LHA for 2025/26 in response to these rising rent costs:

Do nothing: LHA could be frozen at the rate implemented by the previous government.

Do something: LHA could be decoupled from rent costs, but uprated by an alternative measure, such as inflation.

Do the right thing: the link between LHA and the 30th percentile of local rent costs could be maintained.

Fully uprating LHA is the most effective way of supporting private renters in the short term – and probably for the foreseeable future. Measures in the Renters’ Rights Bill will improve housing standards, as well as making it more difficult to evict tenants. But without stronger regulation directly addressing the cost of renting, the problem of increasing housing costs in the PRS has to be addressed through the benefits system. Maintaining the link between LHA and the 30th percentile of local rent costs is a necessary next step.

Re-freezing LHA

Maintaining current LHA rates would not require any increase in planned expenditure on housing cost support. But at a time when private rent costs are rising sharply, re-freezing LHA would cause significant hardship, ultimately putting more financial and capacity pressure on local services insofar as evictions and homelessness would increase.[30] This option should not be considered.

Modelling using the NRI shows that, if LHA rates are frozen, by the end of 2025/25, 93% of people in the PRS, receiving means-tested benefits, will have completely used up the additional income due to 2024 uprating on rent increases experienced in 2024/25 and 2025/26. And for the 7% for whom rent increases over this period do not completely exhaust the increased housing cost support from April 2024 onwards, they would have only £29 per month left to address existing shortfalls.[31]

Uprating LHA by inflation

According to spending estimates published at the Spring Budget 2024, housing cost support for people receiving HB or UCHE in the PRS was forecast to cost around £12.9 billion in 2025/26 (2024/25 terms).[32] With CPI inflation in the year to September 2024 (the reference point for benefit uprating in April 2025) expected to be 2%, housing cost support would cost around £0.3 billion more.[33]

Given that 2% is far short of how much private rent costs have grown in the past year, this option would also cause significant hardship. It should not be considered.[34]

Uprating LHA by rent cost increases

Our strong recommendation is that the government uprates LHA rates in line with how the policy was originally designed, ie the increase in the cost of the 30th percentile rental property in each BRMA (expected to be an average of around 8.24%).

Furthermore, this should be the norm for annual LHA uprating, set aside only in exceptional circumstances rather than reviewed each year. This may commit the government to spending levels dictated by housing market conditions that are relatively unpredictable; however, it would also provide a fiscal incentive for the government to reduce housing costs through action on affordable housing provision and stronger rights for PRS residents.

We estimate this option would cost around £0.6 billion in 2025/26.[35] The average increase in LHA rates across all categories and local rental markets in England, Scotland and Wales in 2024/25 was 16.6%[36], and the cost of housing cost support for private tenants rose by 10% as a result.[37] If the same ratio was repeated in 2025/26, an 8.24% increase in the average LHA rate would result in an increase in spending of 4.98%.[38]

This option is the only course of action available that would minimise hardship for people in the private rented sector on very low incomes. The government should take the opportunity to maintain the link between LHA and rent cost increases at the budget, and confirm that LHA will be uprated by this mechanism each year, for the foreseeable future.

We assume that the national LHA cap would be uprated if this option were chosen – it would need to be removed in full to allow more claimants to access the appropriate LHA rate.

The benefit cap would also need to be significantly uprated or abolished altogether for all claimants to receive housing cost support at the level intended by the design of the LHA system. This would of course increase the cost of uprating LHA rates by any amount, but we are not able to estimate the impact on public spending.

Discretionary support

If LHA is not uprated in full – and even if it is – demand for DHPs is likely to increase. We believe funding for DHPs should be increased even if LHA is fully uprated. Flaws in the LHA system – such as the implementation lag, or the lack of attention to the availability of affordable housing – mean that, for people in the PRS, being able to access HB or UCHE does not guarantee that unexpected housing costs that risk eviction and homelessness can be avoided at all times. This is especially the case if the benefit cap and other restrictions such as the 2-child limit remain in place.

Despite the rising cost of private rents, funding for DHPs has been reduced. It decreased from £140 million to £100 million per year for local authorities in England and Wales in 2022/23, and has been frozen at this level up to the end of 2024/25. Funding for DHPs should be increased.

Other reforms

Uprating LHA is justifiable on its own terms, to help people meet the rising cost of renting privately. However, it is also necessary to compensate for various flaws in the LHA system that mean too often people do not get housing cost support at the intended level.

As indicated above, over the longer term reforming or abolishing the benefit cap would be beneficial to many families – especially larger families, with parents out-of-work, who live in the PRS. This would be the case even if LHA is refrozen or uprated by less than rent costs have increased: other things being equal, it would allow them to access housing cost support at the level implemented in April 2024 in full. Alternatively, the government could consider introducing a benefit cap exemption for families in the PRS.

The government should review how LHA rates are calculated, and consider closing the implementation lag, to ensure that LHA rates implemented each April are a true reflection of housing cost support needs.

In recognition of the unreliability of the SAR in particular, the government could abolish the SAR, allowing under-35s to access the 1-bedroom rate of LHA, at a cost of around £0.4 billion. Alternatively, reducing the upper age limit for the SAR back to 25 would cost around £0.5 billion.[39]

Methodological annex

The analysis focuses on private renters receiving means-tested benefits, specifically Universal Credit (UC), and assesses the potential impacts of policy changes in the 2025/26 financial year compared to 2024/25.

The baseline data (2024/25) was sourced from merged datasets representing rental costs and LHA shortfalls. LHA shortfalls were derived from debt clients' data, and a 5% generosity adjustment was applied to align the average LHA uprating with Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts while preserving the variation across LHA categories observed in the debt client data.

The assumptions underpinning our forecast are: a 2% increase in Universal Credit and non-housing benefit payments; an 8.6% rise in rent costs[40]; and no increase in housing cost support payments. The analysis compared the baseline year (2024/25) with this scenario for 2025/26 by calculating changes in individual expenditures, LHA shortfalls, and deficits.

Results were weighted using survey design methods, with household counts estimated based on DWP figures for Universal Credit claimants. The analysis also quantified the share of households facing deficits and estimated leftover LHA, while accounting for cumulative rent increases across years.

*All names have been changed

This briefing note has been authored by Craig Berry

Notes

The author is grateful to Rachel Beddow, Thomas Hunter, Rebecca Rennison and Julia Ruddick-Trentmann for advice and support with this research.

February 2024. Calculated from Stat-Xplore (UC households table 3: Month by housing entitlement).

February 2024. Calculated from Stat-Xplore (UC households table 3: Month by housing entitlement).

Citizens Advice (2024) The National Red Index, available at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/policy/publications/the-national-red-index-how-to-turn-the-tide-on-falling-living-standards/.

Craig Berry (2023) The Impact of Freezing Local Housing Allowance, Citizens Advice, available at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/policy/publications/the-impact-of-freezing-the-local-housing-allowance/.

Areas with higher employment may have higher rent costs, but not necessarily a higher LHA maximum if they are in the same BRMA as areas with lower employment levels.

FOI 2024/19679. See also Craig Berry (2024) ‘Where have the young renters gone?’, We Are Citizens Advice, available at: https://wearecitizensadvice.org.uk/where-have-the-young-renters-gone-a8cad07f4eb7.

Citizens Advice (2024) The National Red Index, available at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/policy/publications/the-national-red-index-how-to-turn-the-tide-on-falling-living-standards/.

Edward Pemberton and Craig Berry (2024) An Unfair Share: Local Housing Allowance is Failing Young People, Citizens Advice, available at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/policy/publications/an-unfair-share-local-housing-allowance-is-failing-young-people/.

Citizens Advice (2024) Through the Roof: How Rising Rents, Rising Disrepair and Rising Evictions are Pushing Private Renters into Crisis, available at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/policy/publications/through-the-roof-rising-rents-evictions-and-persistent-disrepair/.

Ibid.

Calculated from Stat-Xplore (UC households table 3: Month by housing entitlement). These are households in the PRS receiving UCHE in the PRS in February 2024 with 1, 2 or 3+ children in Central London and Inner North London, and with 2 children in Inner East London and Inner South West London. Our analysis does not take into account the requirement of some children in the same household to share a bedroom (ie 2 children of the same sex aged under 16, and 2 children of any sex aged under 10); this does not affect our estimates for Central London and Inner North London, but does mean that some families with 2 children in Inner East London and Inner South West may only receive UCHE at the 2-bedroom rate, which is not currently capped in these areas.

Calculated from Stat-Xplore (UC households table 3: Month by housing entitlement) and FOI 2024/19679. These are households in the PRS receiving UCHE in February 2024 with no children Central London, Inner North London and Inner East London, excluding those receiving UCHE at the SAR (in November 2023 - the latest available data), which is set below the relevant cap in all BRMAs.

Calculated from English LHA rates available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/664b5562ae748c43d3793e90/england-rates-2024-to-2025-revised.csv/preview, and benefit rates available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/benefit-and-pension-rates-2024-to-2025/benefit-and-pension-rates-2024-to-2025#benefit-cap. We assume the couple (both aged 25+) receives the maximum standard allowance, plus UCCE for 2 children (both born after April 2017). The higher benefit cap in operation in Greater London has been taken into account. This family’s benefit income would breach the benefit cap if they also claimed UCHE at the maximum rate – a reasonable assumption given the high proportion of households for whom the maximum does not cover their rent in full – but it is likely that some families in these circumstances would have sought less expensive properties to rent in response to the benefit cap.

See note 15 for sources and assumptions. The only difference is that the family receives the Universal Credit standard allowance at the single rather than couple rate for people aged 25+.

Although the interaction of LHA and the benefit cap also causes problems for social tenants, when social housing rents are linked to LHA rates. This link should mean rent costs are covered in full, but this is not the case if the household has the benefit cap applied.

ONS data available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/bulletins/privaterentandhousepricesuk/august2024.

Alex Turner (2024) ‘Just 8.5% of private rented homes affordable under uplifted LHA rates, research finds‘, Inside Housing, 20 March, available at: https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/news/just-85-of-private-rented-homes-affordable-under-uplifted-lha-rates-research-finds-85678.

Private rent costs in the UK grew by more than 6% between September 2023 and June 2024. See https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/bulletins/privaterentandhousepricesuk/august2024.

Note that this trend may be due to the declining supply of DHPs due to funding restrictions, as well as an increased demand for DHPs among benefit claimants.

Of 166 responses (excluding ‘Don’t know’ answers), 33 advisers reported a significant increase in the number of people helped, 62 reported a slight increase, and 61 reported no change.

Of the 166 responses (excluding ‘Don’t know’ answers), 38 reported that 90% or more of the people they support in these circumstances had experienced a rent increase, 74 reported this applied to between 60% and 89% of the people they support, and 34 reported it applied to between 40% and 59%.

May 2024. Calculated from Stat-Xplore (UC households table 3: Month by housing entitlement). Note that the new LHA rates would have been uprated for most UCHE recipients by the end of May 2024, although as noted above a small number will not have benefited from the higher rate until early June (the shortfall rate may yet fall slightly further from June onwards, other things being equal – but this is unlikely given that private rent costs have continued to increase).

May 2024. Calculated from Stat-Xplore (UC households table 3: Month by housing entitlement).

Note that the second quarter of 2024/25 includes data up to 31st August.

See Citizens Advice (2024) The National Red Index, available at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/policy/publications/the-national-red-index-how-to-turn-the-tide-on-falling-living-standards/ for an explanation of the NRI and its methodology.

See https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/bulletins/privaterentandhousepricesuk/august2024. The Valuation Office Agency uses different methods to the PIPR to calculate rent cost increases, and in any case changes at the 30th percentile may be different to the change in the UK mean (as well as variable across BRMAs). But we can expect its findings to be broadly similar. For the purposes of illustrating the impact of various LHA uprating options in this section, the 8.24% figure is used.

For example, a failure to adequately uprate LHA is likely to see the cost of providing temporary accommodation to increase. For an analysis of how these costs have increased in recent years, see Hollie Wright (2024) Cost of Providing Temporary Accommodation Skyrocketing for Councils, New Economics Foundation, available at: https://neweconomics.org/2024/04/cost-of-housing-homeless-people-skyrocketing-for-councils.

See the annex for an outline of the methodology.

See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/benefit-expenditure-and-caseload-tables-2024.

To be precise, £258,174,859. This estimate takes no account of the managed migration process in the financial year 2025/26, but there is no reason to believe that migrating claimants from HB to UCHE would make any material difference to housing cost support expenditure. It is also likely to be a small over-estimate; increasing LHA maximum amounts by an average of 2% does not mean that all claimants will receive housing cost support at the maximum rate. However, given that rent costs the majority of claimants are already above current rates, we can assume that most households would claim housing cost support at or close to the maximum allowable amount.

It is possible that a limited increase (or even no increase) in LHA rates would help to constrain future rent rises, since landlords would know that benefit claimants will not be able to afford significant rent increases. However, there is no evidence that this occurred during the 4-year period in which LHA was frozen. And even if it became evident in future in some ways, constraining future rent rises would not help benefit claimants in the PRS to meet the cost of rent increases that have already happened since current LHA rates were determined.

To be precise, £638,644,339.

Calculated from LHA rates available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/universal-credit-local-housing-allowance-rates-2023-to-2024 (2023/24) and https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/universal-credit-local-housing-allowance-rates-2024-to-2025 (2024/25).

Calculated from benefit expenditure data available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/benefit-expenditure-and-caseload-tables-2024.

It is also worth noting however that many more people aged 16-34 are eligible for housing cost support but not claiming it. This is at least in part because they cannot afford to rent a property if only eligible for the SAR. Uprating LHA in April 2024, and especially if repeated in April 2025, may enable more people to claim the support available, resulting in higher public spending. There is no information available publicly about whether this effect was evident after April 2024. However, given that LHA increases lag behind actual rent costs increases, it seems just as likely that some young housing cost support claimants will have needed to give up their rented property to move back into their parental home, resulting in lower public spending.

Edward Pemberton and Craig Berry (2024) An Unfair Share: Local Housing Allowance is Failing Young People, Citizens Advice, available at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/policy/publications/an-unfair-share-local-housing-allowance-is-failing-young-people/. Our cost estimates were based on an SAR caseload of 150,000 people; this is higher than the actual caseload, according to the latest available data, but we should note that more young people may seek to access housing cost support if their relevant LHA rate is increased.

2% is our expectation for the annual change in inflation up to September 2024, with non-housing benefit payments expected to increase by this amount in April 2025. 8.6% is the annual change in average rent costs in the year to July 2024 (ie the latest available data; see https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/bulletins/privaterentandhousepricesuk/august2024).